There are many websites which will give you a detailed medical understanding of glaucoma and its treatment

However, we don’t want to simply duplicate their (extensive) information. What we aim to do is give you an understanding of how glaucoma and its treatment will affect you - the patient - and your family. So we try not to have too many medical diagrams, but will aim to answer questions like how glaucoma might affect your ability to drive, for example, or what to expect during a glaucoma operation

“Glaucoma” is a general term for a number of conditions that affect the optic nerve, often (but not always) associated with increased pressure in the eye.

If you’ve just been diagnosed with glaucoma, then please don’t panic – it is a very treatable condition and the vast majority of people retain good eyesight. It’s very important that the condition is diagnosed and then properly managed – glaucoma can’t be ‘cured’ but the right treatment and/or surgery, regularly reviewed, will allow most people to live a completely normal life.

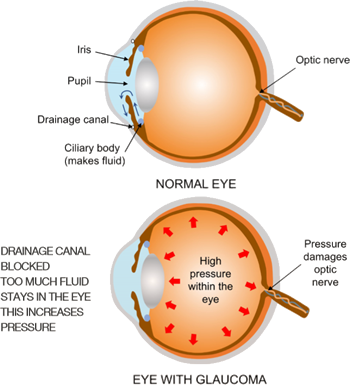

The front part of the eye is filled with a fluid (called aqueous humour), which helps to maintain the structure and health of the eye. This fluid is secreted by a part of the eye called the ciliary body, which is located behind the pupil. The fluid passes through the pupil and drains largely through a microscopic drainage structure called the trabecular meshwork.

High pressure within the eye can damage the delicate nerve fibres which carry the visual signal back to the brain. This damage occurs either as the fibres course along the surface of the retina, or as they enter the optic nerve. This damage causes very characteristic changes in the optic nerve and the visual field.

High intraocular pressure is a strong predisposing factor for developing glaucoma, but it is not the only factor. For example, it is possible to get glaucoma with a normal, or even low intraocular pressure (“normal pressure glaucoma or “NTG”)

Untreated, the raised pressure in the eye will slowly damage the optic nerve in the back of the eye. This damage causes very characteristic changes to the appearance of the optic nerve called “cupping” which the optometrist and ophthalmologist can recognise.

The following figure shows an example of a healthy nerve compared to one from a patient with glaucoma. You can see that in the patient with glaucoma, the nerve tissue (called the rim) is thinned, and that the cup is enlarged.

The optic nerve carries the signals from the eye to the brain, so any damage to the nerve affects the vision. Typically, the field of vision is affected first, often starting from the outside (your peripheral vision).

Surprisingly, many people won’t notice this until a significant amount of vision has been lost (see pictures). The other eye will compensate to a certain extent, and people seem to adapt to seeing less around the edges of their vision than they used to – tragically, some people only notice when their eyesight is extremely badly affected.

Vision lost to glaucoma can’t be restored – the damage is irreversible. Thankfully, in the developed world with modern eye tests and screening, glaucoma is usually picked up before significant damage is done. It is then possible to treat the condition with medication and/or surgery in order to stop it progressing. However, it’s estimated that even in the developed world, 50% of all glaucoma cases remain undetected and undiagnosed (this rises to 90%+ in the developing world). Untreated glaucoma can lead to blindness: it is the commonest cause of blindness in the UK and the second leading cause of blindness worldwide after cataracts. It’s estimated that about one person in 200 under the age of 50 will have glaucoma. This rises to one in 10 over the age of 80.

Increasing age is a major risk factor as glaucoma becomes much more common as we age. The risk of glaucoma is 1-2 per 100 in people aged between 40 and 50. However it rises steadily thereafter by decade, and is estimated to be present in almost 1 in 10 of those aged over 80.

Ethnicity: Anyone of African or Afro-Caribbean descent is also at increased risk of glaucoma. The disease tends to come on earlier and is usually more severe.

A family history of glaucoma is an important risk factor. Individuals with a first degree relative (i.e. parents or siblings) with established glaucoma are at most risk. The risk is highest where a sibling has the condition.

Highly short-sighted patients: Patients who are highly myopic (worse than -6 dioptres) are at increased risk.

Other less well understood risk factors: Diabetic patients may be at slightly increased risk. Patients with high or low blood pressure are at increased risk. Finally, patients who have thinner than average corneas may also be at increased risk.

We do occasionally diagnose glaucoma in patients under 40 years of age, particularly those with other risk factors listed above. Because of this, it is recommended that all individuals over the age of 35 see their optometrist (optician) at least once a year.

There are two main types of glaucoma:

open-angle glaucoma and closed-angle glaucoma (also called angle closure glaucoma).

The “angle” here refers to the angle between the iris (the coloured part of the eye) and the cornea (the transparent front part of the eye) – it’s here that the drainage structure of the eye, known as the trabecular meshwork” is found. This is a very small part of the eye. If the angle is closed, no drainage can take place, while an open angle means that some drainage can occur.

Open-angle glaucoma is much more common in the UK, accounting for over 95% of cases. This occurs when the flow through the microscopic drainage channels (trabecular meshwork) becomes impaired. It’s not known why this happens – age is a factor, and there is a genetic component. The blocked canals result in increased pressure in the eye, damaging the nerve and affecting vision.

Open angle glaucoma is almost always painless, and many people don’t know they have it – unfortunately that’s also part of the problem as it can remain undetected for some time. Fortunately it develops slowly, so regular screening will usually pick it up before serious damage occurs.

Treatment of open angle glaucoma aims to reduce the pressure in the eye by using drops, laser or surgery (for details see below). Other treatments can include ensuring that the blood pressure is well controlled (i.e. not too high or too low), in order to improve circulation.

In this variant of glaucoma, the typical features of glaucoma are seen, with damage to the optic nerve (cupping) and loss of the visual field. However, the intraocular pressure is not elevated.

NTG is more common in women, and the elderly. It is believed poor circulation in the optic nerve is a causative factor. Many patients also have one or more of the following associated conditions: migraine, poor circulation, cold hands or feet (Raynaud’s), poor thirst mechanism, and low blood pressure. Overly aggressive treatment of high blood pressure (hypertension) can also be a factor.

By definition, the eye pressure is normal or low in NTG, and for this reason it can be missed in the community if the optometrist relies too heavily on the puff test as a sole means of detecting glaucoma.

NTG is treated in the same way as normal open angle glaucoma. Although the intraocular pressure is “normal”, the aim of treatment is to lower the intraocular pressure even further to the lower end of normal, for example down to 10 mm Hg or below.

Closed-angle glaucoma is more common in countries outside the UK, particularly Asia, and only accounts for about 10% of the cases seen in the UK. It occurs when the iris (the coloured part of the eye) blocks off access to the drainage channels within the eye. If this occurs acutely, the eye pressure can rise rapidly to levels where is causes pain – IT IS A MEDICAL EMERGENCY. Without prompt treatment sight can be permanently lost.

Early symptoms of closed-angle glaucoma are misty vision and haloes around lights (especially at night). An acute attack will cause pain (sometimes with vomiting and/or nausea) and a red, inflamed eye. Anyone experiencing these symptoms should go to their nearest hospital as soon as possible.

As we mentioned earlier, “glaucoma” covers a number of conditions that result in an increase in eye pressure. Other factors such as injury, growth of new blood vessels or vein blockage (seen in diabetes) can also increase the pressure in the eye and cause glaucoma. These will be treated in a similar way to the more common types of glaucoma given above.

Ocular hypertension is used to describe the condition where there is unusually high pressure in the eye BUT that eye doesn’t appear to have glaucoma. The pressure is outside normal limits but there are no signs of damage in the eye or abnormalities in the field tests. In many cases, ocular hypertension is a mild condition, and the majority of patients won’t develop glaucoma. This is particularly true in patients who have an overall low risk of glaucoma – i.e those with no family history of glaucoma. Many patients may have ocular hypertension throughout their life and never get glaucoma.

In contrast, some patients with ocular hypertension can have a higher risk of glaucoma, particularly those with a strong family history, a thin cornea, or those of Afro-Caribbean or West African ethnicity. These patients need more frequent monitoring and may be offered pressure-lowering treatment to prevent glaucoma.

Your optometrist (optician) will carry out a number of tests to check for glaucoma:

Firstly, as we said before, don’t panic! Glaucoma is very treatable and needn’t cause undue concern as long as it’s properly managed.

The first thing to do is to find an ophthalmologist (eye surgeon) who specialises in treating glaucoma. This is important, as there is a very wide range of medication and procedures/surgery for glaucoma and you will want to get treatment that’s precisely tailored to your condition and your needs.

We would recommend that you ask your optometrist or GP to recommend an ophthalmologist either through the NHS or privately – they will know ophthalmologists specialising in glaucoma who they refer to regularly and trust with their patients. You could also see a specific ophthalmologist who has been recommended to you by family or friends. They should be appropriately qualified (i.e. Fellow of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists) and ideally should hold a substantive NHS consultant post with specialisation in glaucoma. Most ophthalmologists who manage glaucoma patients would have had fellowship training in glaucoma.

No, you can keep leading a perfectly normal life whilst you arrange to see an ophthalmologist.

This depends on a range of factors and personal preferences, so isn’t really a question that we can answer. Both pathways are equally valid. However, there are some facts that you might find helpful:

Once your diagnosis of glaucoma has been confirmed, it’s important to tell your family (parents/ siblings/children) as there is a hereditary component to glaucoma. They should be reassured that there’s nothing to panic about – but they should ensure that they get their eyes tested every year by an optometrist as described above. That way any early signs of glaucoma can be picked up if they were to develop the condition. Given that 50% of glaucoma cases are undetected and it’s the leading cause of blindness in the UK, you may be making a huge difference to their future sight.

Your ophthalmologist should have received information about your case from your optometrist or GP. They will then decide what additional tests are required for your case. They may also repeat some of the tests described above.

These are all painless although be aware that some of the drops used may make your vision blurry - do not drive to or from your appointment, and make sure you are not required to drive for some hours afterwards!

Some of the main tests used are:

Pachymetry and tonometry: The front surface of the eye (the cornea) is numbed with local anaesthetic drops. A small hand-held machine with a blunt end (pachymeter) is brought up to gently touch the surface of the eye. You will not feel it because of the local anaesthetic drops. The pachymeter measures the corneal thickness – this tells your ophthalmologist whether the cornea is thick, thin or average. This gives additional information about your risk of glaucoma and the accuracy of eye pressure readings.

The intraocular pressure in your eyes will be measured using a machine called a tonometer that works in a similar way.

Gonioscopy: Again, this is done when the front surface of the eye has been numbed with anaesthetic drops. The ophthalmologist will place a lens onto the front surface of your eye (cornea) to examine the drainage structure of the eye. This is called the angle - this crucial test will allow the specialist to identify whether you have an open angle, or whether you have signs of narrowing of the angle, predisposing you to angle closure glaucoma.

Examining the optic nerve: If gonioscopy confirms that the angle is open, dilating drops are put into the eye to dilate (enlarge) the pupil, making it easier to see into the back of the eye. These take about 20 minutes to work and will make your vision blurry and slightly sensitive to light. The ophthalmologist will examine the optic nerve at the back of the eye with lenses and a bright light.

NOTE: You cannot drive for a few hours after having dilating drops put in.

Retinal photography/Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): There are various different ways of taking photographs of the back of the eye, depending on what the ophthalmologist needs to examine. All these machines will require you to look into a machine at a fixed point while a photo is taken or a scan carried out. Optical Coherence Tomography uses a very weak and safe laser light to image the back of the eye (retina and optic nerve) in very precise detail. This technology can measure the optic nerve head – this is helpful for diagnosis and also to assess any deterioration.

Visual field analysis: This test is also often done by your optometrist and is described above.

If you are a driver in the UK and have been diagnosed with glaucoma, the DVLA gives clear guidance which you must adhere to. This can be found at the following: www.gov.uk/glaucoma-and-driving or you can contact the DVLA.

Basically, you don’t need to tell the DVLA if you are diagnosed with glaucoma in one eye if the other eye is healthy and has a normal field of vision.

You must tell the DVLA if your glaucoma affects both eyes, or if you have glaucoma in one eye, and a medical condition in the other eye. In this case you can report the condition to the DVLA and they will send you a form to fill in (“Form V1”), or you can download it from the website. Your optometrist, GP, or ophthalmologist can help you to complete the form. The DVLA will then ensure that your field of vision meets the legal requirements for driving. Generally the majority of patients with early glaucoma can continue to drive even if it affects both eyes, but only once they have obtained clearance from the DVLA.

Most other countries will have similar standards.

NOTE: In this section the information comes from our patients and deals with their experience in our practice. This information will be useful for anyone undergoing glaucoma surgery, but details may vary in different practices and hospitals.

The surgeries are commonly performed as a day case procedure, but usually Mark would want to see you the morning after surgery for trabeculectomy and tube surgery. If you travel from afar you may wish to stay overnight.

You will need to report to the hospital 2-3 hours before surgery. You will report to the nursing staff who will take a medical history, record any medications you take, and enquire about any allergies. Please ensure that you mention any blood thinning medications, such as Warfarin that you are taking. Your blood pressure will be measured. Mark will visit you, and answer any additional questions you may have. You will also be asked to sign a consent form, and Mark will mark the forehead above the eye to be operated on. A gown is placed over your clothes.

The anaesthetist will place some local anaesthetic underneath the conjunctiva around the eye. The anaesthetic injection is generally felt as a small sting – a recent survey of patients at Moorfields Eye Hospital found that two-thirds of patients reported little or no discomfort. The local anaesthetic also paralyses the eye, so that you can’t see anything out of it while you’re being operated on. The eye will remain numb for about 6 to 12 hours, so there is no need to be concerned if the operation is delayed slightly. Very anxious patients can be given some sedation as an intravenous injection: this makes you feel relaxed and sleepy during the operation, although you will still be awake. Please ask if you would like this option. Some types of glaucoma surgery (usually tube surgery) are carried out under a general anaesthetic.

NOTE: This is for patients having local anaesthetic only! You will be helped to lie flat on the operating table, made comfortable and your head will be supported

People worry about this – but you will not be able to see the instruments coming towards your eye. You will see very little out of the eye being operated upon due to the anaesthetic which has been administered. In addition, your other eye will be covered with a sterile transparent drape which is slightly frosted (see picture) – so you won’t see instruments out of your other eye, either.

Patients worry about this, but it does not matter as the eyeball being operated on is paralysed temporarily by the anaesthetic. It’s kept moist by the salt water solution. You can blink your other eye as normal.

Patients who have had a general anaesthetic may feel sleepy for a while following the surgery. Those who opted for sedative will find that this wears off quite quickly. You will have a patch on your eye after the surgery, and patients are asked to remove this shortly after waking up on the following morning.

You can go home one to two hours after surgery. Most patients, sensibly, like to have a cup of tea and a light snack or sandwich. You should allow some time for your post-operative drops to be prepared in pharmacy, and for the nurse to go through these drops with you.

It’s a good idea to have a friend or relative with you to help you home. You will have a patch over one eye, which you will be adjusting to, and you may have been given some sedation for surgery. Public transport can be used, but for the reasons given above most patients prefer to leave hospital via car, minicab or taxi. Long journeys are best avoided.

After most glaucoma surgeries you will be seen the next day in the morning, and you need to be able to return to the hospital the next day. Patients who live a long way out of London should make plans that allow for this (either stay overnight in hospital, or in a hotel, or with a friend or relative). Please let us know if this is likely to cause problems and we can work out how best to accommodate your situation.

You can remove the pad over your eye when you wake up the morning after your surgery. Your eye may be a little red and it’s important not to be alarmed by this. The vision may be blurred in the first few days after glaucoma surgery.

You should be able to resume your normal day-today activities within a few days after surgery. You can return to driving if you feel comfortable and you have adequate vision in your fellow eye. It is reasonable to take a few days off work after glaucoma surgery, particularly for glaucoma tube surgery, especially as you may be on quite a number of drops and also you will have fairly frequent post-operative clinic visits. A graded return to work over the first week is sensible, and those with sedentary jobs can be expected to return to work quite quickly. If the eye pressure is low after glaucoma surgery, you will be advised to rest and limit activities.

Mark will prescribe some antibiotic drops and some anti-inflammatory drops for your eye, which usually need to be put in four times a day initially. You continue these drops for approximately one month.

After glaucoma tube surgery it is quite usual to continue glaucoma drops in the initial period, which can be a few months, until the tube begins to work. Please make sure that you will be able to do this following surgery, or ensure that someone will be able to put them in for you.

Many of the precautions are common sense! For 2 weeks after surgery you should avoid:

You will be asked to put a clear shield over your eye before you go to bed, to be worn during the night. This should be done for 1 week after surgery.

It is perfectly safe to fly immediately after surgery. However, Mark insists that patients curtail any travel plans and stay in the UK, able to travel to London, for at least two weeks after surgery. This allows him to see patients if they encounter any post-operative problems.

Please remember that you have had an operation on the eye. You will be using drops and it is expected that the eye will be red and a little sore for a few days after surgery. It is sensible NOT to schedule major life events for 1 - 2 weeks after surgery (e.g. “trip of a lifetime”, distant business trips, weddings, major anniversaries, etc).

After trabeculectomy and glaucoma tube surgery, Mark will review you the next day after surgery and a few days later. Thereafter, you should be prepared for frequent post operative visits in the first 6 weeks after glaucoma surgery, and this particularly applies to trabeculectomy surgery.

You can apply eye makeup 2 weeks after surgery.

It is very common for the operated eye to feel slightly gritty for a while after surgery. This is due to surface dryness and can be alleviated with lubricating eye drops. It occurs because the surface of the eye has been disturbed during surgery, and some of the corneal nerves have been cut.

The symptom of grittiness can easily be treated with lubricating drops, which can be bought at a chemist/ pharmacist without a prescription. Mark recommends “Celluvisc 0.5%, Hycosan or Hylotears”, to be applied 4-6 times a day as needed.

This is normal. You are seeing a patch of donor tissue which is protecting the tube.

If you notice one or other of the following symptoms then you must be seen urgently:

If you have any of the above symptoms, you need to seek advice urgently.

For patients who have had private surgery by Mark Westcott only:

During office hours please contact the practice on Tel: 020 7402 0724, Mobile: 07963 452901.

Alternatively, you can ring Moorfields Eye Hospital on the following number: 020 7253 3411 (24 hours, including weekends) and ask for the Accident & Emergency Department. Explain to them that you are a recent surgery patient of Mr Westcott’s and they will advise. Moorfields Eye Casualty is staffed 24 hours a day by experienced ophthalmologists who can see you in the first instance and who will be able to contact Mark.

We have put all the glaucoma information on this page of our website into a pdf document for you to download and print out if you prefer.